Objects all the way down

Никола Стоянов

Objects exist as autonomous units, but they also exist in conjunction with their qualities, accidents, relations, and moments without being reducible to these. To show how these terms can convert into one another is the alchemical mission of the object-oriented thinker. — Prince of Networks by Graham Harman 1

0. Abstract

In this paper we will be focusing on both Edmund Husserl’s and Martin Heidegger’s monumental work on Ontology, and through it find a way into both Heidegger’s Four-fold (Das Geviert) and the field of object-oriented ontology. We will find our way into this topic through perception, the building block of the phenomenological project. In turn we will show how both Husserl’s and Heidegger’s theory can be pushed into a flat ontology and extend into the realm not only of human being, but of all phenomenon as such. Our guide in this essay will be the reworked four-fold as presented in Graham Harman’s work in “The Quadruple Object” 2. Our main goal is to show how Husserl’s work on finitude has resonated through the field of post-Kantian philosophy to the present day theories of Speculative Realism 3 and thus open a way into both Husserl and the late Heidegger’s work on objects and ontology.  4

4

1. Husserl and the Sensual

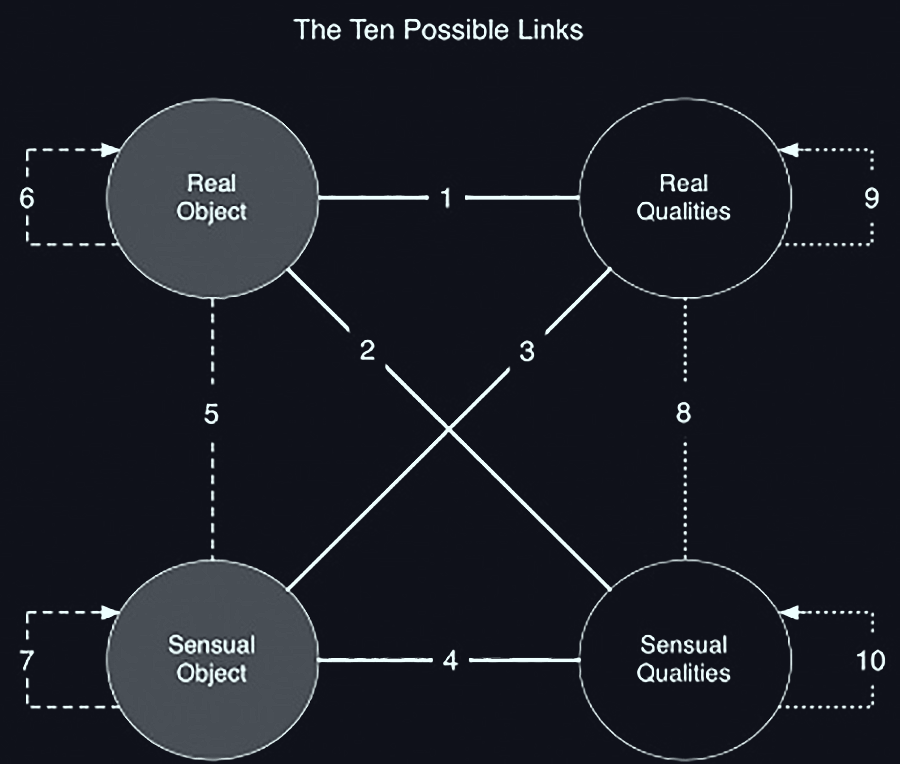

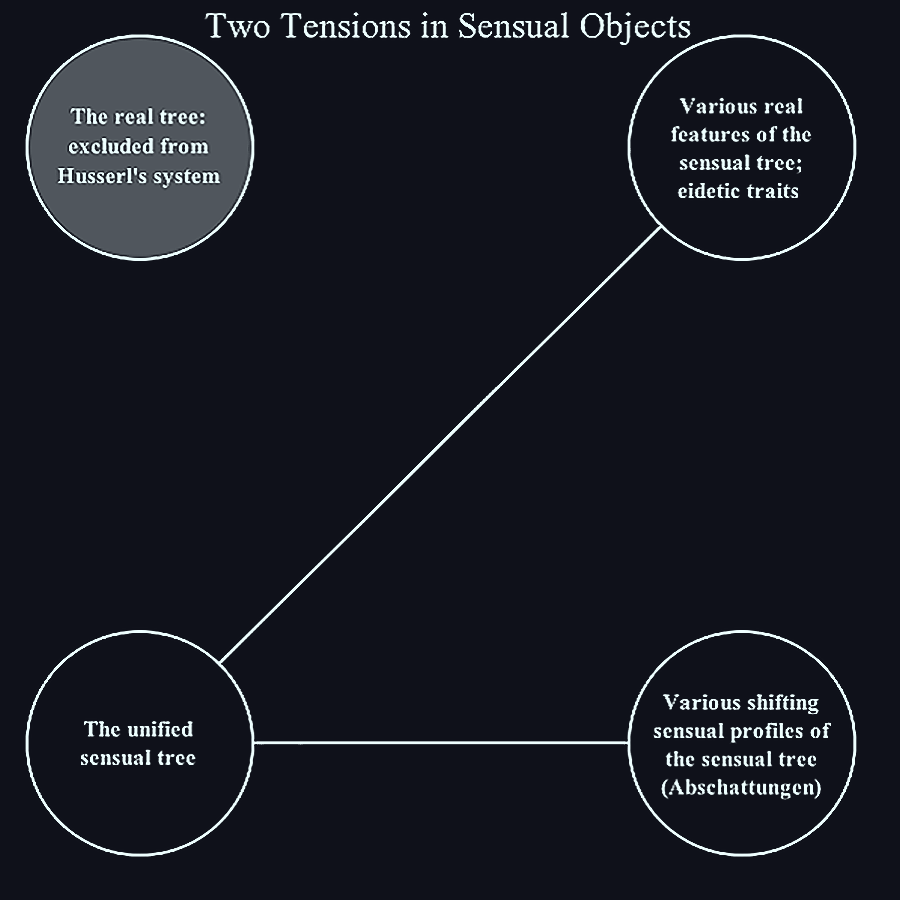

1.1 The tension of the Intentional Realm

To begin we will take a look at Husserl’s formulation of perception as an object-giving act 5 and in turn show how it differs from the positions of both of his tutor Franz Brentano and the British school of empiricism. Like his mentor, Husserl is concern with intentionality in perception and thus with that which the mind is oriented towards, namely some object 67. This is so in both cases of either perceiving an object, like an apple in front of me, or when you feel an emotion and in this it is always directed at some phenomenon. Contrary to empiricism then, for Husserl what comes first, is not qualities or impressions in isolation but an object. An interesting movement that Husserl makes here is that, his idealism does not reject the distinction made by his Polish contemporary Twardowski of object and content 8, but instead of dividing it into, as Kant would do, a world outside and inside the mind, “he imports it into the heart of the immanent realm itself.” 910.This makes Husserl the first object-oriented thinker, even though an idealist. This object that is primal in experience 11, will then become the meting point of two different kinds of qualities, eidetic and accidental 12. This division of object and qualities, inspired by Twardowski is a device Husserl uses to depart from Brentano in thinking that not all intentional life is bound in presentation 13. The following example will make this clear:

To begin we will take a look at Husserl’s formulation of perception as an object-giving act 5 and in turn show how it differs from the positions of both of his tutor Franz Brentano and the British school of empiricism. Like his mentor, Husserl is concern with intentionality in perception and thus with that which the mind is oriented towards, namely some object 67. This is so in both cases of either perceiving an object, like an apple in front of me, or when you feel an emotion and in this it is always directed at some phenomenon. Contrary to empiricism then, for Husserl what comes first, is not qualities or impressions in isolation but an object. An interesting movement that Husserl makes here is that, his idealism does not reject the distinction made by his Polish contemporary Twardowski of object and content 8, but instead of dividing it into, as Kant would do, a world outside and inside the mind, “he imports it into the heart of the immanent realm itself.” 910.This makes Husserl the first object-oriented thinker, even though an idealist. This object that is primal in experience 11, will then become the meting point of two different kinds of qualities, eidetic and accidental 12. This division of object and qualities, inspired by Twardowski is a device Husserl uses to depart from Brentano in thinking that not all intentional life is bound in presentation 13. The following example will make this clear:

Husserl here is more empirical than the empiricism, 14 namely because no matter if we throw an apple in the air, and move as to look at it from different angles, or look at it in different moods, we know and don’t need reassurance that it is the same apple 15. For Husserl objects are perceived only from one perspective of their adumbrations(Abshattung) 16. In this case we never know the fullness of the object, but these present qualities are not just qualities in isolation, as stated before, these adumbration by themselves point to more possible adumbrations, in a system of referential implications (Verweisen) 17, and thus beckon us (Hinweisen)18 to explore the inexhaustible depth of the reality of the object. It is then here that Husserl is even more empirical then the empiricist 19, as he posits the not-visible parts of the object, in experience, as co-present, if only hinted at most of the time, and not “as psychologists have often done, that I represent to myself the sides of the lamp which are not seen” 20.

To repeat our apple example, these adumbrations brought about by the shifting of perspective do not mean that the object becomes a totally different entity, we do not know and need to acquaint ourselves with anew. This leads us to a problem:

If consciousness is always perception of something and in turn is always bound to a limited perspective, how is it possible for us, in our finite position of perspective, to distinguish the set of qualities representing the object in the present circumstance (a part or perspective of it) from the unified object as a whole. Here we encounter another tension, namely that of the unified object in the sense experience, and the multiplicity of shifting qualities that encrust it. How it seems in experience, is that the apple in our example is there from the start, having been given to experience “in one blow”(in einem Schlage) 21, and at the same time containing a halo of potentiality around it, to be adorned by concrete contingent adumbrations 22. For Husserl then adding up all the ways an object presents itself through its qualities (adumbrations) does not exhaustingly describe the object 23 as it has many more not-given perspectives.

What this means for us is that beyond the constantly shifting adumbrations, we are exposed to it in a constant shifting of perspective, what is given in one blow is the unified sensual (in Graham’s terminology) or intentional (in Husserl’s terminology) apple.

1.2 The Tension of Eidos and Intentional Objects

“External perception is a constant pretension to accomplish something that, by its very nature, it is not in a position to accomplish. Thus it harbors an essential contradiction as it were.” 24

This inherent tension has been seen in the realm of the sensual, in our fourfold model. To continue we will inquire into this tension present in the relation to real or eidetic qualities. But these eidetic qualities in contrast to what Husserl believed cannot be intuited theoretically and wont exhaust the object any more, in other words if I strip the apple of all accidental adumbrations by way of eidetic reduction, I do not get a pure empty manifold of an apple. This means that the objects real parts recede from consciousness.

What we observe then is that this tension is in turn a tension between receding qualities and its given concrete adumbrations, always mediated by an object. Thus as Harman notes:

“It seems to me that this is why Husserl feels like a realist: for him, intentional objects are not just bundles of qualities lying before the mind, but places of fracture where an object grinds up against its own qualities, displaying different qualities at different times even while remaining distinct from them.” 25

To follow the trail of this realism in Husserl we need to depart from his idealism by means of the other relation left in the model; namely, the opposite of the link between real objects, and their real and sensual qualities, and thus encounter Heidegger and his famous tool-analysis.

2. Heidegger and the Concealed

“Children are afraid even of those they are best acquainted with, when disguised in a visor; and so ‘tis with us; the visor must be removed as well from things as from persons; that being taken away, we shall find nothing underneath but the very same death…”** 26

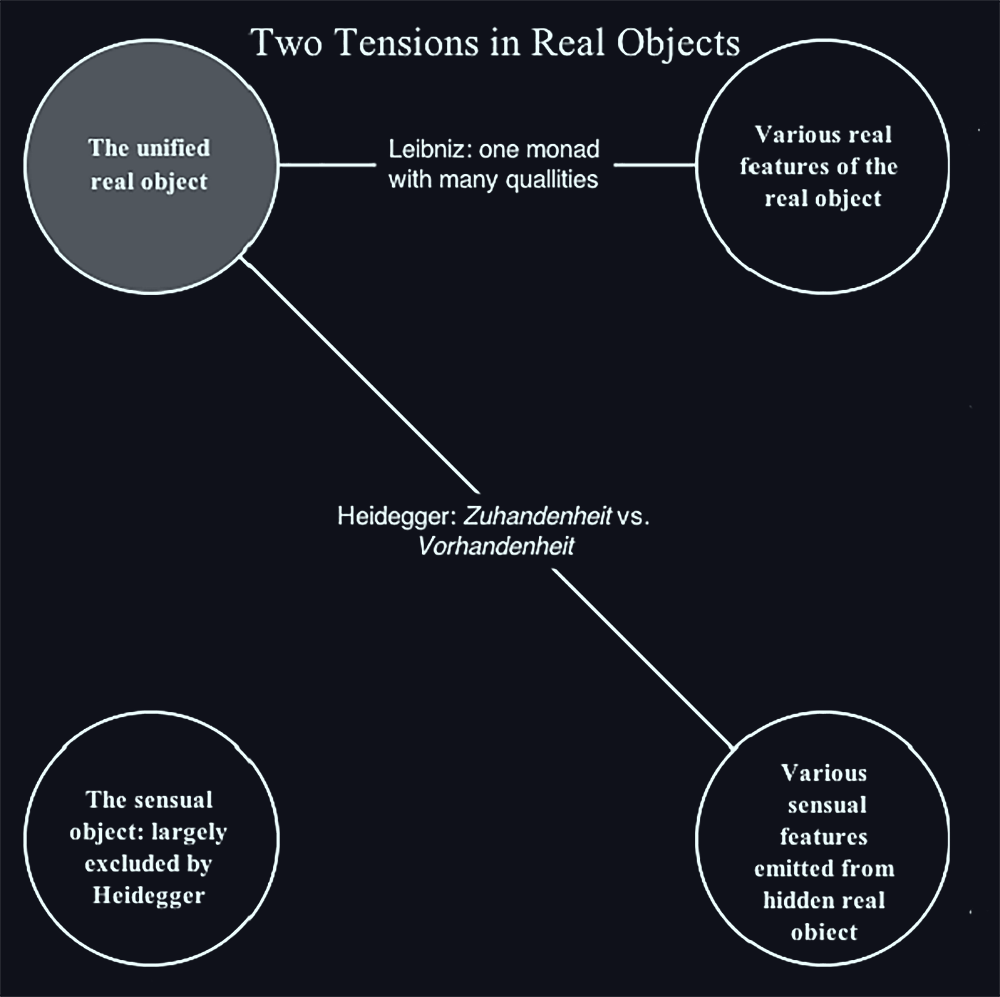

2.1 Vor/Zu – handenheit 27

In his magnum opus Being and Time, Heidegger continues in the tracks of Husserl’s phenomenology, but this time leading it away from the description of things as positively given to us in experience. This he does by virtue of the fact that in our normal mode of being, taking care of things28, they do not appear as present to us in consciousness 29. Here then we will look at another connection in the fourfold, namely connection three on our first diagram. For Heidegger the things that are closet to us in our every-day being-in-the-world are taken for granted and relied upon 30, things such as the oxygen in the air, the floor’s capacity to endure weight, or the relative political stability of the region in which I am writing this 31, lead us, in the way they give themselves to us, into the famous tool-analysis. The tool-analysis shows that in our everyday use of tools we mostly rely on them while they stay unnoticed32, on the other hand revealing themselves in their brute details, only when they break down 33. Examples of organs, bus routes and so on, show us that when they break such objects do not lose their character of having been useful (ready-to-hand), but present themselves in exactly the opposite manner, namely as obstacles to handiness, present-at-hand in the form of brute concrete adumbrations 34.

In his magnum opus Being and Time, Heidegger continues in the tracks of Husserl’s phenomenology, but this time leading it away from the description of things as positively given to us in experience. This he does by virtue of the fact that in our normal mode of being, taking care of things28, they do not appear as present to us in consciousness 29. Here then we will look at another connection in the fourfold, namely connection three on our first diagram. For Heidegger the things that are closet to us in our every-day being-in-the-world are taken for granted and relied upon 30, things such as the oxygen in the air, the floor’s capacity to endure weight, or the relative political stability of the region in which I am writing this 31, lead us, in the way they give themselves to us, into the famous tool-analysis. The tool-analysis shows that in our everyday use of tools we mostly rely on them while they stay unnoticed32, on the other hand revealing themselves in their brute details, only when they break down 33. Examples of organs, bus routes and so on, show us that when they break such objects do not lose their character of having been useful (ready-to-hand), but present themselves in exactly the opposite manner, namely as obstacles to handiness, present-at-hand in the form of brute concrete adumbrations 34.

Thus these two modes of being, called ready-to-hand (zuhandenheit) and present-at-hand (vorhendenheit), are not only the main modes in which objects get given to us, but also the main way they interact. Here we will continue in this analysis to show that it can be driven further to encompass not only human-being (Dasein) but all objects including, cities, communities, individuals, cars, cloud formations, weather systems, rocks, atoms, quarks. Our way into flat ontology then consists in showing how the hammer in both cases of its breaking-down, because of Dasein, and because of other objects never loses it ready-to-hand (zuhandenheit) character.

On the one hand we have the inter-Dasein relationship where if we take the example given by Husserl, of his close friend Hans, we will see that we do not totally define Hans by the way he looks,(by a bundle of qualities he has) but I still know it is him, how he feels, if he is injured, mainly through how he presents himself to me, meaning this part is inseparable the same way it is for Husserl as it is what is given as concrete details, present and real 35. We can see that this does not exhaust him, as even if such situations were repeated numerous times, as in the case of a long friendship, there are still traits I do not know about my close friends, from anything like how he will act during a civil war, to if he is going to back-stab me if engaged in the proper circumstance.

On the other hand, we have the fact, contrary to what a pragmatist reading of the tool-analysis would impart, that both theory and praxis do not exhaust an object fully 36 or in other words, eating an apple, does not exhaust it any more than having a theory of agriculture about it. To continue with this example, in both cases what we do, is we paraphrase the apple through specific adumbrations, ie. its power to feed me, or its qualities described in the context of nutrition science or agriculture, as in both cases we never grasp all potential of the apple, only those that are useful or evident. What this would entail then is that even if the apple is burned it does not lose its ready-to-hand status, but only reveals such and such qualities before receding back into the core of the real object 37.

“The tribesman who dwells with the godlike leopard, or the prisoner who writes secret messages in lemon juice, are no closer to the dark reality of these objects than the scientist who gazes at them. If perception and theory both objectify entities, reducing them to one-sided caricatures of their thundering depths, the same is true of practical manipulation.” 38

Here we get into the realm of vicarious causality and see that if pushed enough Heidegger’s tool-analysis breeds a strange kind of occasionalism, that does not demand a ‘magical being’ to ensure cause but is deployed locally 39. In our reading then we encounter another problem, namely how is causation possible, when things in their normal being interact only on the outer layer of the objects halo of possibilities, revealing for a short while its core, in the requiem of its usefulness, only for it to recede back into its murky depths.

2.2 The interior of object

To return to Husserl, like Brentano he holds that the mind is the only thing that holds an object, and thus distinguished it from physical reality. We have already departed from these figures by showing how Dasein and object are on the same footing. What is left to be shown is that every interaction of objects not only happens on the interior of another object but always breeds a new object in the process. Having shown how Heidegger might have misinterpreted his own insight, and having shown that being is no slave to Dasein, we come to the strange position where both an object is both different from its relation with other such objects and its inner relation with its parts. Heidegger would have us believe otherwise as for him such an isolated tool does not exist, a tool is always caught up in a referential matrix 40, it is always in the plural 41. But isn’t the tools breakage exactly what displays the fact that it has never been fully integrated into its usefulness, it is not an image one can use constantly without wearing it down, or changing it 42. Thus the apple is more than its uses, and on the other hand as shown before it is not its pieces or qualities that are evident. On one hand then, the object cannot exist as an undefined lump without qualities but can still sustain change in them and sustain itself as the same object 43, something known sometimes as redundant causation 44.

3. A polypsychismic ontology

The finitude that is at the base of all object relations then shows that humans have no privileged ontological status to rocks, birds or planets. This might seem naive as only a fool would deny our superior cognitive skills to an apples, but what is meant is that, the gap stands between an object and its relations, not us and objects. This reversal of the Kantian revolution, which was falsely named a Copernican one, will then consist in the moving of man away from the center of the universe 45 Here is where our occasionalism lies, to reverse Kant, and open up a way into a democratic model of objects. As we have said this occasionalsim is deployed without relying on onto-theological devices, not even on Dasein. This has been shown through the fact that objects are not exhausted by either their relations (an apple will not stop being on a table even if some of the tables qualities always shift slightly) or us as privileged beings and thus what we are left with is an ontological polypsychism, where object cannot be undermined by empirical sciences or overmined by structural theories so prevalent today 46 47.

4. Conclusion

In this essay we have shown how Husserl’s conception of the finitude and failure of perception 48 to grasp objects can be made into a universal ontological principle. This we have done through mapping the found relation to the reworked four-fold and thus finding a way into how it might be understood. Contrary to the post-Kantian movement our interpretation has moved man away from the position of being a base for all relations and helps fill in the holes left open on the question of the ontological status of beings, like animals 49 present in Heidegger’s later works. How then object-oriented ontology doesn’t relapse into the basic ontological rift of subject and object so common in other modern theories and keeps its modern credibility in light of its, albeit local and occasionalist model of causality, has thus been shown.

Footnotes

Graham Harman, Prince Of Networks (Prahran, Vic.: Re.press, 2009). p.156 ↩

Graham Harman, The Quadruple Object (Winchester, U.K.: Zero Books, 2011). p. 87-91 ↩

For a general introduction to Speculative Realism watch Graham Harman’s Lecture Speculative Realism, 2013, European Graduate School, can be accessed at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hK-5XOwraQo ↩

Diagram made by Michael Flower and taken from Graham Harman, The Quadruple Object p.78 ↩

Graham Harman, The Quadruple Object. p.23 ↩

Edmund Husserl, Analysis Concerning Passive And Active Synthesis (Illinois USA: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2015)., p. 40 ↩

Graham Harman, ‘The Road To Objects’, Continent, no. 13 (2011). p. 173. ↩

Kazimierz Twardowski and Reinhardt Grossmann, On The Content And Object Of Presentations (The Hauge: Nijhoff, 1977). ↩

Graham Harman. The Quadruple Object. p.23 ↩

Graham Harman, Bells And Whistles (Winchester, U.K.: Zero Books, 2013). p. 23 ↩

Edmund Husserl, Analysis Concerning Passive And Active Synthesis , p. 44 ↩

Diagram made by Michael Flower and taken from Graham Harman, The Quadruple Object. p.33 ↩

Graham Harman, The Quadruple Object. p.31 ↩

Graham Harman, On the horror of phenomenology: Lovecraft and Husserl, Collapse VI, 2010-03-08 p. 21 ↩

Edmund Husserl, Analysis Concerning Passive And Active Synthesis , p. 41 ↩

Ibid., p.39-40 ↩

Ibid., p. 41 ↩

Ibid., p. 42 ↩

Graham Harman, On the horror of Phenomenology: Lovecraft and Husserl, Collapse VI, 2010-03-08 p. 20-21 ↩

Maurice Merleau-Ponty and James M Edie, The Primacy Of Perception, n.d. 13-14 ↩

Dermot Moran, Edmund Husserl (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2005). p. 158 ↩

Edmund Husserl, Analysis Concerning Passive And Active Synthesis, p.54-55 ↩

Ibid, p. 39 ↩

Ibid, p. 38 ↩

Graham Harman, The Road to Objects, Continent, Issue 1.3 / 2011, p. 173 ↩

Michel de Montaigne, William Hazlitt and O. W Wight, Works, Comprising His Essays, Journey Into Italy, And Letters, With Notes From All The Commentators, Biographical And Bibliographical Notices, Etc (New York: Hurd and Houghton, 1864), p.144 ↩

Diagram made by Michael Flower from Graham Harman. The Quadruple Object, p. 48 ↩

Martin Heidegger, Joan Stambaugh and Dennis J Schmidt, Being And Time (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2010), p. 66-67 ↩

Martin Heidegger, Being And Time, p. 69 ↩

Ibid., p. 68 ↩

Graham Harman, Greenberg, Heidegger, McLuhan, and the Arts, Lecture, PNCA MA in Critical Theory and Creative Research program, College in Portland, Oregon, January 22, 2013. ↩

Martin Heidegger, Being And Time, p. 67 ↩

Martin Heidegger, Being And Time, p. 73 ↩

Ibid., p. 74 ↩

Graham Harman, Bells And Whistles. p. 22-25 ↩

Martin Heidegger, Being And Time, p.69 ↩

Ibid., p.73 ↩

Graham Harman, On Vicarious Causality, Collapse, Issue 2, 8/2/2007, p. 193 ↩

Graham Harman, On Vicarious Causality, p. 172 ↩

Martin Heidegger, Being And Time, p. 82 ↩

Ibid., p. 68 ↩

Graham Harman, Time, Space, Essence, and Eidos: A New Theory of Causation, Cosmos and History: The Journal of Nature and Social Philosophy, vol. 6, no. 1, 2010, p. 4 ↩

Graham Harman, The Quadruple Object. p. 56 ↩

Manuel DeLanda, A New Philoshophy of Society, London: Continuum, 2006, p. 37 ↩

Graham Harman, The Quadruple Object. p. 45-46 ↩

Ibid., p. 111-113 ↩

Ibid., p. 7-20 ↩

Edmund Husserl, Analysis Concerning Passive And Active Synthesis, p.22 ↩

Martin Heiddger, The Fundamental Concepts of Metaphysics: World – Finitude – Solitude. Translated by W. McNeill & N. Walker. (Bloomington, IN: Indiaa University Press, 2001.) ↩